edited by the Legal Agenda

Pre-auditing, which involves verifying the legality of financial transactions and their conformity with the budget before they are carried out, is one of the main consuming roles of the Court of Accounts (CoA). The CoA Organization Law states that “the CoA’s pre-auditing is a procedure essential for any deal or transaction subject to this auditing to take effect. Any transaction that does not undergo this auditing is considered void, and the relevant official may not put it into effect”. If the CoA withholds approval, the administration must comply, unless the Council of Ministers adopts an explained decision allowing it to bypass the rejection, as we shall explain later in detail.

Because most administrative transactions cannot be executed without undergoing CoA pre-auditing, this auditing is classified as one of the CoA’s “administrative auditing” functions, which are distinct from “judicial auditing” functions. In general, the standards governing supreme councils and bodies that perform financial auditing constrict pre-auditing powers in order to consolidate their judicial role. This is evident, in particular, from Principle 3 of the Mexico Declaration issued by the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI). This principle states that one of the essential requirements for supreme audit institutions to be independent is that, rather than auditing government policy, they restrict themselves to auditing the implementation of policy except in cases where the law requires them to do the former.

Another important requirement is that supreme audit institutions should not be involved nor seen to be involved, in any manner whatsoever, in the management of the organizations that they audit. This principle has been reflected in several demands and recommendations to abolish the CoA’s pre-auditing and limit its role to administrative post-auditing and judicial auditing. These demands have been translated into many efforts over the years. They included a bill that the Council of Ministers adopted on 12 December 2000, based on a proposal by the minister of finance, to amend the Public Accounting Law and abolish the obligation to obtain prior approval.

Despite this international trend and these multiple demands, recent legislative trends have reaffirmed the pre-auditing role, particularly due to the ineffectiveness of after-the-fact accounting and the lack of any effective financial oversight inside the administrations subject to audit. Even if this form of auditing is retained, several issues remain standing in relation to the way it is conducted and, most importantly, the executive branch’s ability to override a decision to withhold approval and thereby have the final say.

This administrative auditing became even more problematic when the criteria adopted for conducting it – namely that the monetary value of the transactions exceeds a certain threshold – became ineffective because of the collapse of the national currency. Moreover, pre-auditing is imposed on some public law entities or entities that receive public funds not via a legal text but via decrees adopted by the executive branch. Hence, the CoA’s powers are not fixed by law; rather, some of them can be expanded or constricted by the executive branch.

Before discussing these issues, we will first discern the volume of pre-auditing.

The Volume of Pre-Auditing

The CoA’s reports show that the number of pre-audits has steadily increased over the past decades. While 1,600 occurred in 2001, the number had increased to 2,756 by 2013 and to 3,055 by 2015. We have no figures for subsequent years as the CoA ceased issuing reports.

This twofold increase is explained by the following factors. Firstly, the monetary thresholds for pre-auditing had not been amended since 1997 despite the inflation that occurred since that time. The collapse of the national currency significantly worsened this issue, rendering all financial transactions subject, in principle, to pre-auditing. Secondly, state spending increased from USD6.6 billion in 2001 to USD17.5 billion in 2017, the first year in which an annual budget was drafted in 12 years. Thirdly, the scope of the bodies subject to pre-auditing was expanded to include new municipalities.

Many of the judges whom we interviewed confirmed that pre-auditing consumes a significant portion of the CoA’s efforts and thereby limits their ability to conduct post-auditing, which many of them say is supposed to be their primary work.

This imbalance is evident from the figures that appear in the “annual” report for 2013, 2014, and 2015. Pre-auditing decisions numbered 8,378, whereas decisions related to judicial auditing of officials – including temporary and implicit decisions [i.e. approvals resulting from the CoA’s failure to issue a decision by the legal deadline] – numbered 268. Meanwhile, decisions related to judicial auditing of accounts numbered just 12, and administrative decisions related to auditing accounts numbered 17. Conversely, the report does not mention the issuance of any special reports, which constitute another kind of administrative post-audit.

What Does Pre-Auditing Encompass?

What transactions are subject to pre-auditing? What are the entities whose transactions are subject to it? Is pre-auditing limited to the legality of the transactions, or does it also address whether the reciprocal obligations are balanced or appropriate?

The Monetary Threshold

The first criterion adopted to determine which transactions are subject to pre-auditing is the value of the transaction, which must exceed a certain threshold. The threshold defined in Law no. 286 of 1994, ranged between LL5 million for revenues, LL15 million for amicable settlements of legal cases or disputes, and LL75 million for procurements of works and supplies. In other words, when the threshold was set in 1997, it ranged from the equivalent of USD3,300 to USD50,000. Despite inflation over the past decades, no amendment to this threshold was made until 28 November 2024. Hence, the scope of pre-auditing in practice expanded to include transactions that are less valuable than the legislation intended.

This criterion became virtually ineffective following the collapse of the national currency that began in October 2019. Consequently, the CoA became burdened with low-value transactions. Nevertheless, no legislative amendment to the threshold was made until 28 November 2024, i.e. five years after the crisis began.

Regarding the post-2019 financial collapse, three attempts to reduce the number of transactions presented to the CoA were made.:

The first was a memorandum issued by the CoA’s president on 20 February 2024. It stipulated that purchases with an invoice need not be presented to the CoA if their value is less than LL500 million. Irrespective of the pertinence of this memorandum’s content, the CoA president clearly has no power whatsoever to amend the threshold as, in practice, such an amendment exempts the CoA from responsibilities set for it by law. Despite the memorandum’s illegality, some of the CoA’s chambers followed it (others refused to accept it).

The second was a decision, adopted by the government in its 14 August 2024 session, not to present purchases that are made via a request for quotations and are valued at no more than LL5 billion (approximately USD56,000) to the CoA for prior approval. Via this decision, the government freed itself, along with all the administrations subject to the CoA’s auditing, from this auditing for all transactions involving less than the aforementioned amount, contrary to an explicit legal text subjecting them to it. At the time, the Legal Agenda expressed its concern that this government decision would lead to legal chaos as it illegally suspends an essential procedure and thereby enables any interested party to contest the validity of the exempted transactions.

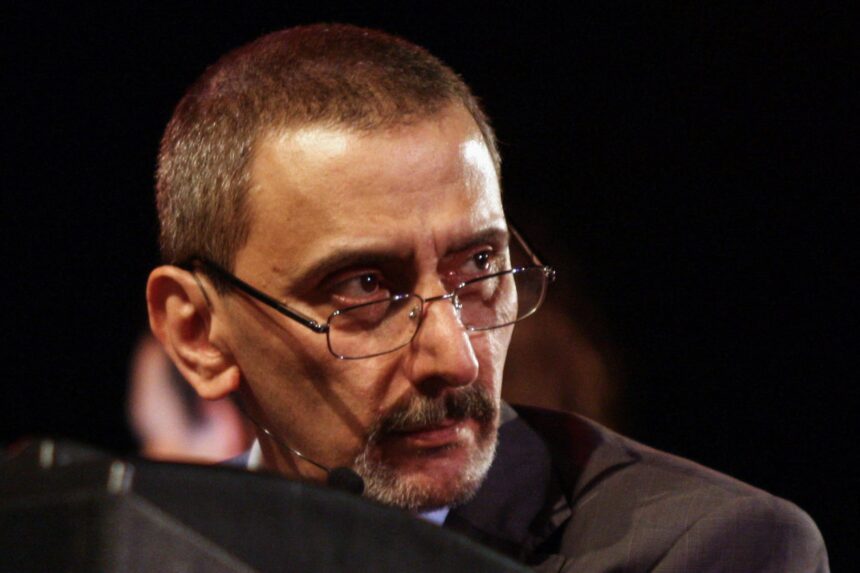

The third attempt was a bill submitted on 23 July 2024 by MPs belonging to several blocs: Ibrahim Kanaan, Hassan Fadlallah, Mohamad Khawaja, Bilal Abdallah, Ali Hassan Khalil, and Jihad al-Samad. The bill aimed to increase the threshold of transactions subject to the CoA’s pre-auditing by 200 to 1000 times. It was adopted recently in the legislative session held on 28 November 2024.

The Entities Subject to Audit

Although the law subjects all public administrations to pre-auditing, the legislators explicitly exempted some public law persons, particularly public institutions and state-owned companies. They justified this exemption with the need to create more flexible frameworks for administering certain sectors. Moreover, in some categories of public law persons (such as municipalities and those that receive public funds), the law leaves it up to various other sources to determine which ones are subject to CoA auditing and the auditing mechanism, thereby depriving the CoA of its authority as an oversight and judicial body with universal jurisdiction.

In fact, General Statute for Public Institutions no. 4517 of 72 exempts public institutions from pre-auditing. Only two institutions are excluded from this exemption, namely the Lebanese University and the Lebanese National Higher Conservatory of Music (their establishment decree subjected them to it). This exemption not only enables these public institutions to spened without pre-auditing but also enables public administrations, in several cases, to evade pre-auditing by transferring their allocated funds to these institutions and delegating them to spend these funds.

For example, the Council for Development and Reconstruction has taken up many projects that fall within the purview of administrations, institutions, and ministries after receiving funds from them for this purpose. Similarly, the Ministry of Telecommunications recently attempted to transfer funds allocated to it to the board of Ogero, allowing the latter to spend them without pre-auditing. The CoA addressed this matter in a decision issued on 29 August 2024, which stated that “the power granted to the minister of telecommunications is connected to the privileges of public authority, is an indivisible whole, and may not be delegated to other bodies in the absence of a law to this effect”. The decision added, “Any relinquishment by the ministry of its powers to Ogero’s board is risky, given the difference between the auditing regulations governing the Ministry of Telecommunications and those governing these boards”. Commenting on this decision, the Legal Agenda said that the CoA had deemed transferring power in this manner to be defective not only because it violates the law but also because it constitutes a fraudulent circumvention of its auditing, although it avoided using the term “fraud” in order not to offend the telecommunications minister.

As for the municipalities, the CoA Organization Law defines the municipalities subject to pre-auditing – namely Beirut, Tripoli, El Mina, Bourj Hammoud, Sidon, and Zahle-Maalaka – but allows the executive branch to subject other municipalities to it via a decree if their revenue exceeds LL1 million. Accordingly, several decrees have been issued subjecting approximately 50 municipalities (i.e. no more than 5% of all municipalities) and a number of municipality unions to this auditing. Hence, major municipalities such as Hazmieh, Baabda, and Jounieh are still exempt from auditing because of the government’s failure to adopt decrees subjecting them to it, which reflects much selectivity in this regard.

The same goes for the companies, institutions, and associations in which the government owns shares, as well as the state’s oversight authorities. While the scope and procedures for auditing these bodies were supposed to be defined by a decree adopted by the Council of Ministers, to this day no decree has been issued. Hence, the provisions of Decree no. 13615 of 1963 remain in force, limiting the auditing of these bodies to post-auditing.

Some bodies also remain exempt from pre-auditing because they do not fall into any of these categories. For example, the text establishing the High Relief Committee failed to define its legal nature, thereby placing it outside the scope of a pre-auditing.

The 2012 bill aimed to plug these gaps by putting all municipalities and municipality unions under the CoA’s jurisdiction. It also sought to significantly amend the companies subject to CoA auditing such that they include any company in which the state, a municipality, a public institution, or legal persons subject to CoA auditing own at least 40% of the shares.

The bill also expanded the CoA’s powers to include auditing concession accounts.