The Beirut Port explosion on August 4, 2020, remains one of the most devastating disasters in Lebanon’s history, killing over 200 people, injuring thousands, and ravaging large parts of Beirut. Five years later, achieving justice for victims has been extraordinarily difficult due to deep-rooted systemic issues in Lebanon’s political and judicial landscape. The investigation has faced repeated obstructions, politicization, and delays that highlight why accountability remains elusive.

Arrests, charges and indictments to date

By 1 September 2020, 30 people had been arrested including the current and former customs chiefs Badri Daher and Shafik Merhi, former port director Hassan Koraytem, Abdel Hafiz Kaissi, director of land and maritime transport at the public works ministry, which nominally oversees the port, and Anthony Salloum, head of the military intelligence at the port. Other prominent persons arrested in connection with the explosion are Brigadier General Antoine Salloum, Major Daoud Fayyad, Major Joseph Al-Naddaf and Major Charbel Fawwaz. In addition, Interpol issued red notices for the arrest of the owner of the Rhosus, Russian national, Igor Grechushkin, the captain of the ship, and Russian national Borys Prokoshew, and a Portuguese national Jorge Moreira.

By mid-October, 30 people had been charged, and Judge Sawan had heard the testimonies of 47 witnesses. According to judicial sources, the charges included ‘willful negligence that led to the deaths of hundreds of innocent civilians and injury of others’ and ‘causing massive destruction to public and private property.’ By mid-November, Prosecutor Ghassan Khoury charged a total of 33 persons in relation to the explosion, including senior customs official Hani Hajj Shehadeh and former customs chief Moussa Hazimeh. The investigating body has also recognized the Management and Investment Administration of the Beirut port as a legal person who can be held responsible for criminal negligence.

The Judicial Council was expected to release an investigation report in mid-November 2020. However, on 7 November 2020, the Higher Judicial Council issued a statement announcing cooperation from the US, UK and French embassies in the investigation, and acknowledging the receipt of the US FBI report by the Lebanese judiciary. Until November 2020, the Judicial Investigator had pressed charges against low-level and mid-level officials only. Not a single minister, former or sitting had been questioned as a suspect, although Judge Sawan heard testimony from current and former ministers as “witnesses” in cases against port and other administrative employees.

In April 2021, six people were released with the approval of the judge. In June 2021, Judge Tarek al-Bitar (the current investigating judge) referred requests to release 19 individuals who were detained in relation to the explosion. Of these, the court released seven. The court refused to release senior port and customs employees.

IV. Role of ministers and immunity

High level government officials, including multiple ministers and President Michel Aoun were aware of the presence of the ammonium nitrate and the risks posed by the substance. Al Jazeera reported,

“Official correspondence between various branches of government, the judiciary and security officials show the president, prime minister, top security officials, members of the judiciary and more than a half-dozen ministers knew the large amount of explosives were at Beirut’s port but failed to take action.”

On 25 November 2020, in his letter, Judge Sawan noted that ministers and officials of the departments of Finance, Public Works, and Justice may be implicated for negligence. Judge Sawan requested the Parliament to do what it deems appropriate in accordance with the Lebanese Constitution in relation to trying former and sitting ministers. Articles 70 and 71 of the Lebanese Constitution stipulate the procedure for levelling charges and initiating legal action against former and sitting ministers of the Parliament.

In response to Judge Sawan’s request to question the former ministers, the Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament stated that such a step does not respect the principle of separation of powers stipulated by the Lebanese Constitution. Further, the Speaker noted that Judge Sawan violated Article 80 of the Constitution, which stipulates that it is the task of the Supreme Council to try Presidents and Ministers.

Article 70 of the Lebanese Constitution provides that the Parliament may accuse the Prime Minister and the ministers of committing high treason or breaching their duties, and it is not permissible for the indictment to be issued except by a two-thirds majority of the total members of the Parliament. If indicted, they will be tried before the ‘Supreme Council to Try Presidents and Ministers.’ The Supreme Council to Try Presidents and Ministers is a special body stipulated under Article 80 of the Lebanese Constitution which comprises Parliamentarians and eight judges; the Supreme Council’s conviction decisions are issued by a majority of ten members.

In December 2020, Judge Sawan summoned Lebanon’s caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab, former minister Ali Hassan Khalil, and former Public Works Ministers Ghazi Zaiter and Youssef Finianos for questioning the following week. None of the four former ministers appeared for questioning, claiming immunity. Ministers Ali Hassan Khalil and Ghazi Zaiter accused Judge Sawan of violating the constitution on the grounds of immunity and moved to the Cassation Court to have him removed from the case. Notably, Judge Sawan’s decision to charge the ministers drew criticism from several political and religious leaders who expressed solidarity with the ministers and called Judge Sawan’s attempt to indict them a violation of the Lebanese Constitution. The Interior Minister Mohammed Fahmi publicly announced his decision not to carry out Judge Sawan’s orders. He said,

In December 2020, Judge Sawan summoned Lebanon’s caretaker Prime Minister Hassan Diab, former minister Ali Hassan Khalil, and former Public Works Ministers Ghazi Zaiter and Youssef Finianos for questioning the following week. None of the four former ministers appeared for questioning, claiming immunity. Ministers Ali Hassan Khalil and Ghazi Zaiter accused Judge Sawan of violating the constitution on the grounds of immunity and moved to the Cassation Court to have him removed from the case. Notably, Judge Sawan’s decision to charge the ministers drew criticism from several political and religious leaders who expressed solidarity with the ministers and called Judge Sawan’s attempt to indict them a violation of the Lebanese Constitution. The Interior Minister Mohammed Fahmi publicly announced his decision not to carry out Judge Sawan’s orders. He said,

“I certainly will not ask the security services to implement a judicial decision of this kind, and [Judge Sawan] can pursue me if [he] wants.”

Alternatively, the Lebanese Parliament has attempted to create a special judicial body to try the former ministers.

In February 2021, following the decision of the Cassation Court of Lebanon, Judge Sawan was relieved of his role in the investigation acting on the complaint of the two former ministers. The court cited conflict of interest because Judge Sawan’s house was damaged in the explosion, and Judge Bitar was named his successor. See Independence of the Investigating body section below.

The resistance put up by the Lebanese government under claims of Parliamentary immunity continues to stifle the investigation process. Following suit from his predecessor, Judge Sawan, once again, Judge Bitar called in Prime Minister Hassan Diab and the other ministers for questioning. He also issued a request to question Nouhad Mashnouq (former Interior Minister) in relation to the case. He also asked the government and the Interior Minister for permission to question two of Lebanon’s most prominent security chiefs – the head of General Security Directorate, Major-General Abbas Ibrahim, and the head of State Security, Major-General Tony Saliba.

As Judge Bitar’s request lay before the sitting Interior Minister, Nouhad Mashnouk hosted a press conference on 23 July 2021 where he observed that he received a document about the Rhosus, the vessel carrying the ammonium nitrate, and its contents in 2014. He reportedly asked, “What the nitrates are for.” The answer he received was always “a substance used in agricultural fertilizers.”

In parallel, the Interior Minister, agreed to authorize questioning of the head of General Security Director, only to change his position and deny the request.

As of 29 July 2021, the Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament stated that Parliament is ‘ready’ to lift the immunity against former Prime Minister Hassan Diab and the former ministers who have been summoned by the investigating body. It is unclear how the readiness of the Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament to lift the immunity will manifest and who it will favor.

The following table represents the names of high-level officials (former and sitting) who were sought by Judge Sawan and Judge Bitar for questioning since November 2020.

| Name | Official title | Status |

| Hassan Diab | Caretaker Prime Minister (Former) | Immunity |

| Ali Hassan Khalil | Finance Minister (Former) and current Parliamentarian | Immunity |

| Ghazi Zeaiter | Public Works Minister (Former) and current Parliamentarian | Immunity |

| Youssef Finianos | Public Works Minister and Transportation Minister (Former) | Immunity |

| Nouhad Mashnouq | Interior Minister (Former) and current Parliamentarian | Immunity |

| Abbas Ibrahim | Head of General Security | Immunity |

| Major General Antoine Saliba | Director General of State Security | Questioned twice |

| Major Joseph Al Naddaf | Head of Port State Security Office | Questioned; detainee |

| Major General Walid Salman | Army Chief of Staff (Former) | Questioned |

| General Qahwaji | Army Chief (Former) | Questioned as witness |

| Badri Daher | Customs Chief | Questioned; detainee |

| Yaacoub al-Sarraf | Defense Minister (former) | Questioned as witness |

| Bassem el-Kaissi55 | Director General of the Port | Questioned |

Key Dates and Investigation Milestones:

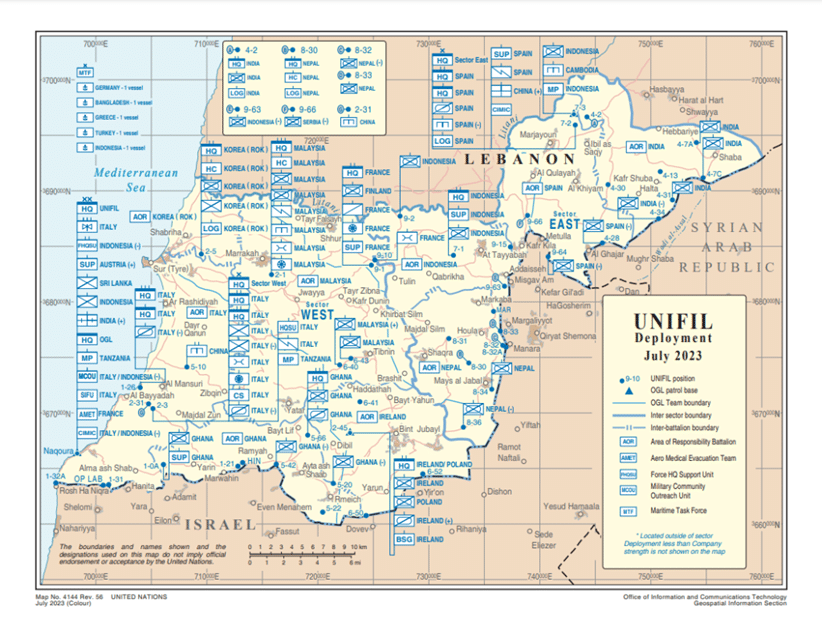

- August 4, 2020: The explosion occurs due to the ignition of approximately 2,750 tons of poorly stored ammonium nitrate in Warehouse 12 at Beirut Port, triggering a massive blast equivalent to 1.5–2.5 tons of TNT.

- August 5, 2020: The Lebanese government orders house arrest for sixteen port officials and arrests the general manager of the port, Hassan Koraytem, and customs officials Shafiq Merhi and later Badri Daher. The government launches three coinvestigations: administrative, military, and judicial.

- Late August to November 2020: Judicial investigations led by Judge Fadi Sawan begin, with arrests of 30 individuals ranging from customs chiefs to military officers. Charges include willful negligence causing deaths and massive property destruction. However, no ministers or senior officials are interrogated as suspects, only as witnesses.

- April – June 2021: Six detainees are released with judicial approval; requests to release additional detainees are also made with rejections for key port and customs officials. Political and procedural hurdles mount, impeding progress.

- December 2021 – January 2023: The investigation effectively stalls due to political interference and judicial conflicts. Attempts by Judge Tarek Bitar, who replaced Sawan, to resume proceedings are blocked, notably by then Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat.

- January 16, 2025: After nearly two years of inactivity, the investigation officially resumes under Judge Bitar following the formation of a reformist government. Ten individuals, including security, customs, and military personnel, are summoned for questioning.

- May 12, 2025: Reports confirm Judge Bitar’s plan to issue an indictment on August 4, 2025—the blast’s fifth anniversary—after completing investigations into the ammonium nitrate’s origin and management.

- August 4, 2025 (Upcoming): The much-anticipated date for indictment release coinciding with the disaster’s fifth anniversary, symbolizing a potential turning point in accountability.

Why Justice is Not Easy and Investigations Are Politicized and Dragging

- Deep Political Entanglement and State Capture

The port and customs administrations were under the control or influence of powerful political and militia groups, including Hezbollah, implicated in corruption and smuggling that allowed hazardous materials to accumulate unchecked. The political elite’s stake in maintaining power structures has fueled obstruction and interference in the investigation. - Judicial Weakness and Interference

Lebanon’s judiciary is seen as compromised, overburdened, and prone to political influence. Key figures like Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat have conflicted interests, at times obstructing investigations directly. Judges leading the case face immense personal and institutional pressure, including attempts to remove Judge Bitar. - Immunity and Legal Hurdles

Several politicians and former ministers implicated have parliamentary immunity, which shields them from prosecution. Legal challenges and complaints brought by powerful individuals have stalled proceedings extensively. - Multiple Investigative Bodies, Complex Processes

Overlapping administrative, military, and judicial investigations have created confusion, inefficiencies, and delays. Administrative and military probes were largely inconclusive and overtaken by the judicial investigation led by Judge Bitar, which is the only active probe presently. - Fear and Intimidation

Witnesses and whistleblowers often face threats, discouraging testimony. Judicial actors also face security risks, restricting free investigative work. - Public Distrust and Political Deadlock

Lebanon’s fragmented political system and governance paralysis have eroded public trust in institutions, contributing to protests demanding justice but simultaneously limiting the ability to enforce accountability. - International Pressure and Limited Cooperation

Though external entities like the FBI and international embassies have cooperated, Lebanon’s government initially refused an international independent probe, citing sovereignty. This has limited forensic transparency and independent oversight.

Summary: Nearly five years after the Beirut Port explosion, justice remains delayed due to entrenched political interests, legal immunities, compromised judicial independence, and systemic corruption. The investigation is a rare test of Lebanon’s judiciary and political will. The planned August 4, 2025 indictment could mark a moment of reckoning, but long-term accountability will depend on sustained pressure for judicial independence and reform amid a volatile political environment.

Key Sources for Further Reading:

- Wikipedia: 2020 Beirut Explosion and Investigation Timeline

- Human Rights Watch: Beirut Blast Investigation Resumes, January 2025

- Legal Action Worldwide: Report on Lebanese Legal System Failures (2021)

- Arab Center Washington DC: Investigation Resumption Analysis (May 2025)

- RFI: 5 Years After the Beirut Port Explosion (August 2025)

- Timep.org: Joint Letter to Protect Investigation from Interference (March 2025)

- This Is Beirut: Detailed coverage on investigation status and politics